The energy transition in Vietnam is happening at an unprecedented speed and scale.

The energy transition in Vietnam is happening at an unprecedented speed and scale. Within 2 years (2019-2020), the renewable energy share in the power mix has increased from negligible amounts to 25% of installed capacity (~17 GW out of 68.9 GW), mostly from solar farms and solar rooftops. According to the latest update in January 2021, the total installed capacity of Vietnam’s power system reached 68.9 GW, of which accounted for 31%, followed by hydropower (30%), solar (25%), gas (10%), oil (2%) and wind (1%).

By the end of 2020, about 11.8 GW of wind power projects had been added to the Power Development Plan (PDP) and the MOIT has proposed a list of 136 projects with a total capacity of 6.5 GW to be included in the PDP. For solar power, the total capacity included in the PDP is 19.1 GWp (15.3 GWac) by the end of 2020 and MOIT has proposed a list of 54 projects with a total capacity of 7.1 GWp (5.7 GWac). In 2020, the Party and the Government have introduced significant directives changes in power development policies of Vietnam with support for the development of RE in the short- and long-term orientations.

Key Challenges

** Published April 2021

For investment, the regulatory risks, capital access possibilities and power market risks are the most prominent challenges. Some factors that can create power market risks include (i) limited grid capacity; (ii) Discontinous tariffs schemes and unclear roadmap for RE auction mechanisms; (iii) delays in large projects due to the complex regulatory framework (LNG, grid infrastructure); and (iv) uncertainty in future energy prices. Feed-In Tariffs have so far worked well to initiate investment streams for RE, but their lifetimes are limited. Now the government is becoming explicit about auctions and portfolio standards are also mentioned. There are also regulations supporting RE development. However, they have been implemented as “stop-and go” policies which could push investors away in the future or limit investors to those who accept high-risk markets in Vietnam. Electricity prices, which are regulated by the government, do not offer long-term outlook on prices, which makes the energy transition unstable.

The limited capital access to invest in grid infrastructure, demand-side management and energy efficiency projects or to increase the flexibility of power plants is a barrier for the power system to meet the technical requirements that are needed in the context of the rapidly increasing shares of renewable energy. The grid infrastructure upgrades are required simultaneously to the supply growth, which is challenging as it is unlikely that the Treasury will take on more national debt to invest in infrastructure. In addition, the monopoly mechanism applied for transmission grid investments does not allow the private sector to invest in this area. The state utility and de facto-monopolist Vietnam Electricity (EVN) has been facing difficulties to get an agreement on the location of substations and transmission lines with local authorities. In addition, there is a delay in the development of the transmission grid which is caused by site clearances and disputes over compensation rates for local communities.

There are some automation solutions that can enable demand-side management which is needed for Vietnam. They include net billing schemes and advanced forecasting of variable renewable power

- Letter no.10052/BCT-DL dated 28th December 2020 of MOIT to the Prime Minister on reviewing the list of wind power projects under the direction of Prime Minister, comments from Central Economic Committee and National Assembly’s Economic Committee.

- Letter no.84/BCT-DL dated 7th January 2021 of MOIT to the Prime Minister on the results of reviewing the list of solar power projects nationwide

generation, as well as new business models that are closely linked to digitalisation such as energy as a service (EaaS), electric vehicle smart charging, artificial intelligence or big data. Vietnam, however, lacks finance resource in the long-term and market design regulatory schemes to implement such solutions. The flexibility of the power system is low which can be attributed to the use of outdated technology in large power plants and ineffective operation mechanisms. Most of the large power plants are governed by generation companies (GENCOs) of the EVN group and the current financial status does not allow GENCOs to get loans directly from commercial funding without a government guarantee.

Innovative solutions to address power market risks and possibilities for capital access require changes in the regulation framework and in the role of actors in the power market.

Market entry may not immediately look like a challenge as the share of RE in the market is quite large and as Vietnam sets ambitious targets for RE development. The proposed capacity of solar and wind has reached dozens of GW and according to the VCE10 list of top 10 emerging enterprises in Vietnam, the share of operating solar capacity of these companies is 49% and the share for onshore wind power is 28%. High market concentration in the VRE sector can however lead to market manipulation. The conditions in the power purchase agreement do not meet international standards and the curtailment that is applied to VRE power plants creates a market entry barrier for newcomers.

Regarding supply chains, hardware availability is a key challenge as almost all components for RE are imported. The supply of hardware might cause delays and additional costs as the limited time to apply to FIT prices can cause time pressure for the design, to open EPC bids and to place orders, which can affect the quality of equipment as well as enhance technical errors. In the long-term, these factors will create risks for investors, banks, buyers, and the power system in general. Adding to the hardware availability challenge, the shortage of skilled labour force in RE industry is also a key barrier for accelerating and ensuring a just energy transition.

Several challenges have been identified regarding grid integration. The most prominent are monitoring and control and reducing the use of dispatchable plants. When it comes to monitoring, systems are in place for system operators, except for hourly planning. However, this data is not publicly available. In addition, the lack of a forecasting system, especially short-term, makes the integration of VRE (wind and solar) in the power system even more difficult. The National Load Dispatch Centre, an EVN’s subsidiary who is the system operator, is now contracting to develop a power generation forecasting system for renewables. Reducing the use of dispatchable plants is a real challenge for the integration of VRE. Overload transmission grid, ensuring system adequacy and profitability of must-run power plants (i.e., Build-Operate-Transfer [BOT] coal/gas power plants) lead to the operation of these plants as baseload. When VRE share increases, it means the coal and gas Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) may have to be renegotiated away from must-run statuses (i.e., BOT power plants), which is not an easy task as this would directly affect the profitability of such plants.

Vested fossil-fuel interests create considerable inertia that is slowing down the energy transition. The 3rd-latest draft of the Power Development Plan (PDP8) shows a large portion of LNG capacity planned and some new coal power capacity after 2030. The share of fossil fuel-based capacity is planned to reach 48% of total system capacity by 2030 according to the selected scenario in the draft PDP8 with about 17 GW of coal and 20 GW of oil and gas thermal to be added in the next 10 years. Of this, 14 GW of added coal capacity and 16.7 GW of added gas capacity will run on imported fuels. This implies a geopolitical dependency of the power system on imported fuels (coal, LNG), which is deeply related to the issue of energy security. It furthermore increases the risk of lock-in of fossil fuel infrastructure developments as the levelized cost of electricity generation from solar and wind energy will be significantly lower than those from coal and gas in Vietnam (Danish Energy Agency, 2019) and the environmental standards will only get stricter. Another key challenge from this aspect is that there is not yet a sufficient consideration for thejust transitionpolicy with no clear action plan to support the transition in the communities in which livelihood depends on fossil fuels (e.g., miners). Such a policy is needed to gain acceptance and support which in turn is needed to accelerate the transition process.

- VCE10 is a list of top 10 Leading clean energy enterprises in Vietnam 2019. The VCE10 was published by Vietnam Energy Magazine in December 2019.

There is a wide range of sectors that are involved in the energy transition process (power, industry, transport, construction, etc) where cross-sector misalignment can be observed. The existing linkages of these sectors on energy transition is weak as they are often managed by different ministries. The coordination scheme among ministries and agencies on clean energy (i.e. MOIT, MOC, MOT…) is still inadequate. Moreover, the sectoral planning processes are not well-integrated. The year 2020 marks the end of a planning period. Hence, prior to this milestone, the government has started the development of many important national plans, of which the National Master Plan is the umbrella of other plans as stipulated in the Planning Law no.21/2017/QH14 which took effect on 1 January 2019. Accordingly, the sectoral plans such as the Power Development Plan the Energy Development Plan detail the National Master Plan according to sectors on the basis of sectoral and regional integration related to infrastructure, use of natural resources, environmental protection, and biodiversity conservation. However, while the task of developing the Power and Energy Development Plans was approved in October and December 2019 respectively, the approval of the task to develop the National Master Plan has only been issued in October 2020.

The transparency on energy-related data also needs to be improved as there is not yet an official information system available for public access. The national energy balance and some basic energy statistics have only been published recently by the General Statistical Office of Vietnam for the period of 2015-2018. Aggregated national data on the power system (i.e. power mix in term of installed capacity and electricity generation) is only published annually by EVN in their annual reports. MOIT published some power sector data on their website to enhance the transparency of the electricity and gasoline business, which include the electricity tariff, electricity transmission price and the quarterly share of electricity purchased from difference sources (hydro, coal, oil, gas, import and other). However, all of the data published are fragmented and lack granularity. In 2018, MOIT has issued the Action Plan to establish the Vietnam Energy Information System with support from the EU. The timeline for completing such a system will be by 2024.

Another challenge in this category is the stakeholders’ knowledge gap. There is a different understanding of stakeholder groups on energy-related issues. Especially between official staffsfrom the Ministry of Industry and Trade and other ministries (i.e. Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Ministry of Transport…), the Central Economic Committee and National Assembly. These gaps pose a challenge for the communication among ministries, legislative bodies and other agencies in the policymaking processes such as harmonising the sectoral plans and developing or revising related laws/regulations that affect the energy transition process.

Windows of Opportunity

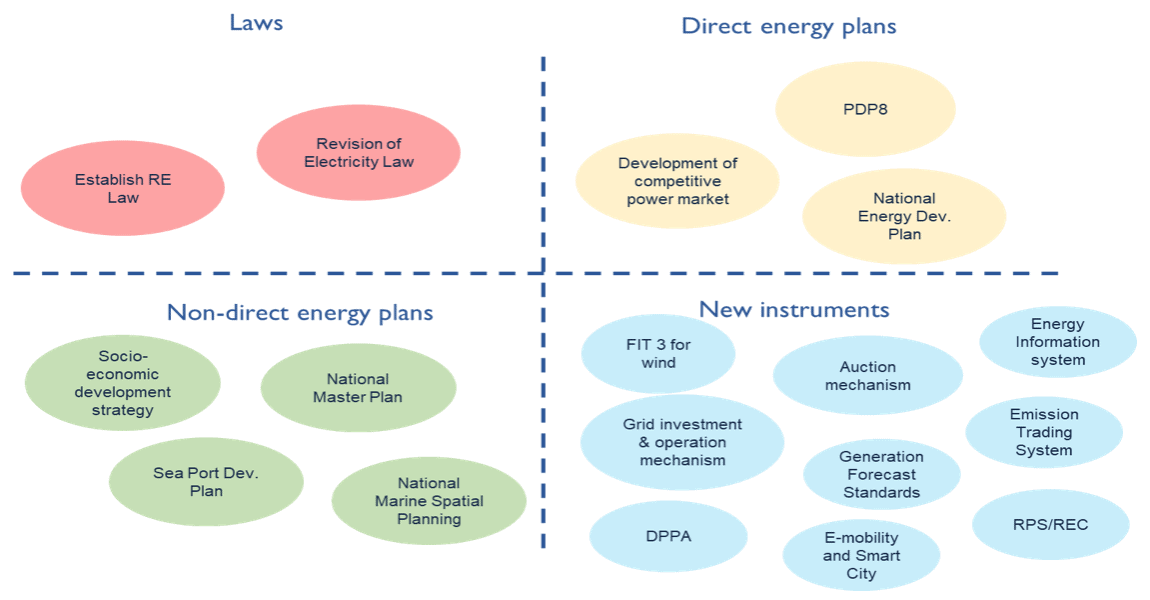

Figure 21 shows the key processes related to energy transition in Vietnam classified in to four categories: (i) Laws, (ii) Direct energy plans, (iii) Non-direct energy plans and (iv) new instruments in energy/power sector in the 2021 – 2025 period.

Figure 21: Windows of opportunity for the energy transition in Vietnam

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on own research

Laws: From the mapping process of the key processes, the country team has identified several windows of opportunities for CASE activities in Vietnam. It starts at the highest level of the legal documents which are stipulating the whole power sector – the Electricity Law. CASE VN would like to support the revision of the Electricity Law in a way that facilitates the mobilisation of private finance in power infrastructure development while maintaining an adequate level of energy security. Another important process is the crafting of the Renewable Energy Law to have a comprehensive set of regulatory instruments to orient the development of the renewable energy sector in a sustainable and effective way. It is expected that the process of revising/drafting these laws will commence in the last quarter of 2021 and finish in 2023.

Direct and non-direct energy plans: Vietnam is in the “planning period” where important national development plans are being constructed for the next decade with visions to 2045-2050. The National Energy Master Plan and the Power Development Plan have been drafted for approval and published for public comments. The CASE country team has been implementing actions to provide comments for these key plans as the window of opportunity is closing. Other national plans relating to the energy transition include the National Master Plan that orients the spatial development of socioeconomic aspects, the National Marine Spatial Plan and the Sea Ports Development Plan. The timeline for completing the National Master Plan is before April 2023. The task of constructing the National Marine Spatial Plan is not yet approved by the government. For the Sea Ports Development Plan, the draft has been completed and presented in the consultation workshops in December 2020 and January 2021. The draft has not yet been published for public comments. The roadmap to establish a fully competitive power market is also critical for the energy transition with the last level – competitive retail market – to be piloted in 2021.

New instruments: Policy instruments are being developed for the transformation of the energy/power sector such as auctioning mechanism and piloting Direct Power Purchase Agreements, which aim to create fairness and competitive power markets in general and renewable energy markets in particular. The ongoing development of the Vietnam Energy Information System is to enhance the transparency in energy-related data for all stakeholders. Other mechanisms to be developed or considered include the new grid investment and operation mechanism, standards for power generation forecast, electric vehicles, renewable portfolio standards, and emission trading systems.