Despite the large potential for renewables

Despite the large potential for renewables, the government’s target to achieve 23% of renewables by 2050 and first promising steps towards increased sharesof renewables, fossil fuels still dominate the Indonesian energy system, both in terms of primary energy and in power generation. Renewables share in the primary energy mix by 2019 was 9.2%, while coal, oil and gas accounted for 37.3%, 35% and 18.5% respectively (Kementerian ESDM, 2019). In terms of power generation, the renewables installed capacity was only 10.5 GW by 2020 out of the total installed capacity of 71 GW (data until June 2020) (Kementerian ESDM, 2020a) and renewables contributed for 14.9% of the electricity generated by the first semester 2020, with coal share being 50% (IESR, 2021)

Key Challenges

* Published April 2021

Energy transition is currently happening around the world, with several developed and developing countries leading the way. In Indonesia, however, this concept is relatively new and there is still much to be learned from the early adopters, including concepts and theories, technology transfer and adaptation, roadmaps, and policy support.

Data and information management, in relation to staff rotation, is another concern in accelerating the energy transition in Indonesia. Many staff in certain positions (or divisions) have benefitted from training related with the energy transition but are then moved to other positions (or divisions) without knowledge transfer. This creates gaps at the institutional level, and poses a strategic concern to maintain developed knowledge levels.

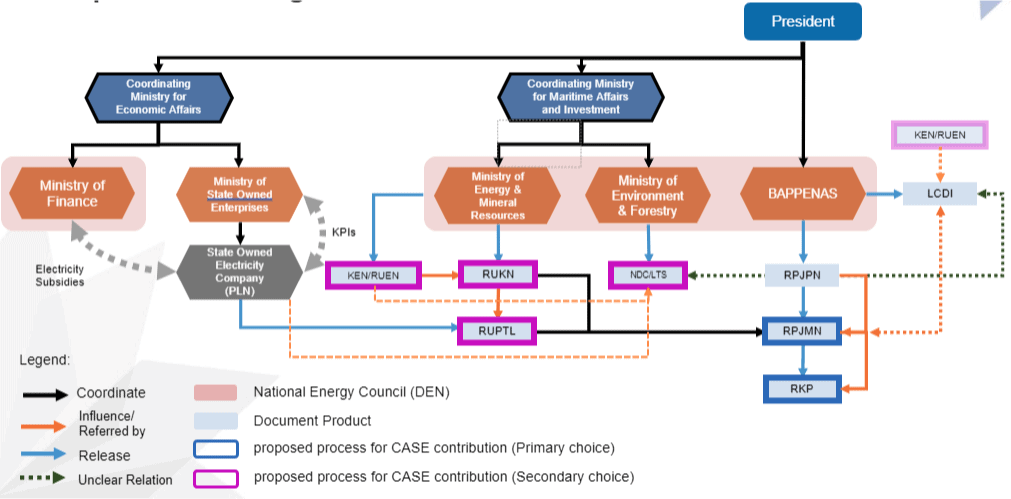

The energy transition is a multi-sectoral task. However, in Indonesia, regulations published by one ministry, for example, will not guarantee full support from other ministries. Each ministry can have ownership of their own programs, but none oversees the whole energy transition process. This creates cross-sector misalignment & policy inconsistency between different sectors and stakeholders involved in energy sector policymaking in Indonesia. Due to this misalignment, there is a lack of cohesion between the various energy strategies, for example between Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), Rencana Umum Energi Nasional (National Energy Plan/RUEN), Rencana Umum Penyediaan Tenaga Listrik (Electricity Supply Business Plan/RUPTL), etc.

Prior to the Pandemic, Indonesia was expected to experience economic growth above 6% with massive expansion in the industrial sector. In 2015, the Indonesian government announced the ‘35 GW programme’ which focuses on building power plants – mostly in Java-Bali – to fuel this growth, 60% of which were supposed to be Coal Power Plants.

However, the fact that the actual economic growth in Indonesia has been limited to 5.03% over the last five years has caused overestimation of power demand (Wold Bank, 2021). This has worsened by declining power demand during the covid-19 pandemic and led to the current oversupply situation in Java area. As a result, policymakers are tasked to look for “demand creation”, to utilise the existing (coal) electricity.

The above-mentioned conditions are also worsened by the fact that the vertically integrated utility PT PLN is obliged, as per the Indonesia Government mandate, by take or pay agreement when signing Power Purchase Agreements. Thus, PT PLN has to buy electricity generated from power plants even when it is not used by the consumers.

As per December 2019, 96% the of 35 GW Programme had reached Power Purchase Agreement level, meaning that the programme implementation will remain the main power sector priority until at least 2028 (Kementerian ESDM, 2020b).

Large capacity fossil fuel power plants are mostly concentrated in Java and Sumatra, where the demand for electricity is high. Meanwhile, on other islands, the demand and installed capacities are smaller. This resulted in a high electrification ratio on Java and Sumatra compared to other islands. With more than 17,000 islands spread across the archipelago, it is challenging for Indonesia to fully integrate its transmission infrastructure. So far, only large island systems like Java, Sumatra, and Bali are planned to be interconnected. The electrification challenge remains for the rest of Indonesia, especially the eastern remote islands.

Based on data from the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR), at the end of 2020 99.2% of the population had access to electricity. The two provinces in the eastern part of Indonesia, which comprise of many islands, have the lowest rural electrification ratios: Maluku at 92% and East Nusa Tenggara at 88%.

The eastern part of Indonesia actually has a big potential for renewable energy and solar PV is already more competitive in cases where diesel or small (inefficient) plants are used. However, the government still sees the small electricity demand in eastern Indonesia, e.g. for industry, as a hurdle to develop renewable energy.

The progress of renewable energy development in Indonesia has been sluggish in the past decade. This is largely due to the lack of financing instruments available for projects in Indonesia.

Out of the 75 Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) signed between 2017-2018, 27 PPAs have not reached financial close (FC) and five projects were terminated. While the regulations seem to hamper access to funding, some IPPs managed to get finance from lenders through the use of a creditworthy project sponsor which a small-scale IPP usually does not have (IESR, 2019).

All in all, a survey conducted by IESR in 2018 indicated that securing finance for renewable energy projects in Indonesia is difficult. Local banks still perceive them as risky and thus charge high interest rates and offer challenging conditions: Debt to equity ranges from 60:40 to 70:30 and local banks rarely offer project finance for both large- and small-scale renewables projects (IESR, 2018).

6.Low ease of doing business (market entry barriers, etc.) and insufficient business environment (financing / power market / regulatory risks)

Overall, doing business in Indonesia is challenging. Import of equipment underlies currency risks as most equipment needs to be imported. Additionally, foreign loans are mainly based in USD which create repayment uncertainties.

Power Purchase Agreements (PPA) include government “force majeure”, which further reduces the bankability of PPAs due to additional threats and uncertainties it brings.

Windows of Opportunity

CASE activities in Indonesia seek to provide research and evidence to support:

- Mid-term National and Planning and Long-term Regional Planning (RPJMN and RPJPD) under the Ministry of National Development Planning/Bappenas

- National Energy Policy (KEN) under the National Energy Council/DEN

In its implementations, CASE Indonesia provides a platform for dialogues, assistance, workshops and training among energy and non-energy stakeholders. For example the Indonesia Sustainable Energy Week, a flagship event of CASE Indonesia, will take place in the second half of 2024.

To raise the awareness of the public, CASE Indonesia conducts various digital campaigns and builds relationships with the media. One such example is the making of the third Kiara Campaign in 2024.

Windows of opportunity for the energy transition in Indonesia

Following a series of coordination meetings with key stakeholders including MEMR, MEF, PLN and MoF, CASE will focus primarily on planning documents released by BAPPENAS. National documents under MEF were not chosen because the development process of this LTS is relatively exclusive. As for the current energy and electricity planning in Indonesia under MEMR tend to use a pragmatic approach that considers the current pandemic condition in Indonesia which requires massive amounts of state budget to quickly recover the economy. As a consequence, it is expected that plans to increase the share of renewable energy will be challenging, at least until the completion of the 35 GW mega project by the end of 2028.

Based on this condition, the CASE Indonesia team set another strategy to change the Indonesian narrative towards the energy transition: to strengthen the background study for RPJMN or RPJP in order to increase the commitment to renewable energy and climate action. Through RPJMN or RPJP, CASE ID can provide a long-term strategy of the energy transition that can influence derivative regulations in Indonesia both for mid- and long-term policy.